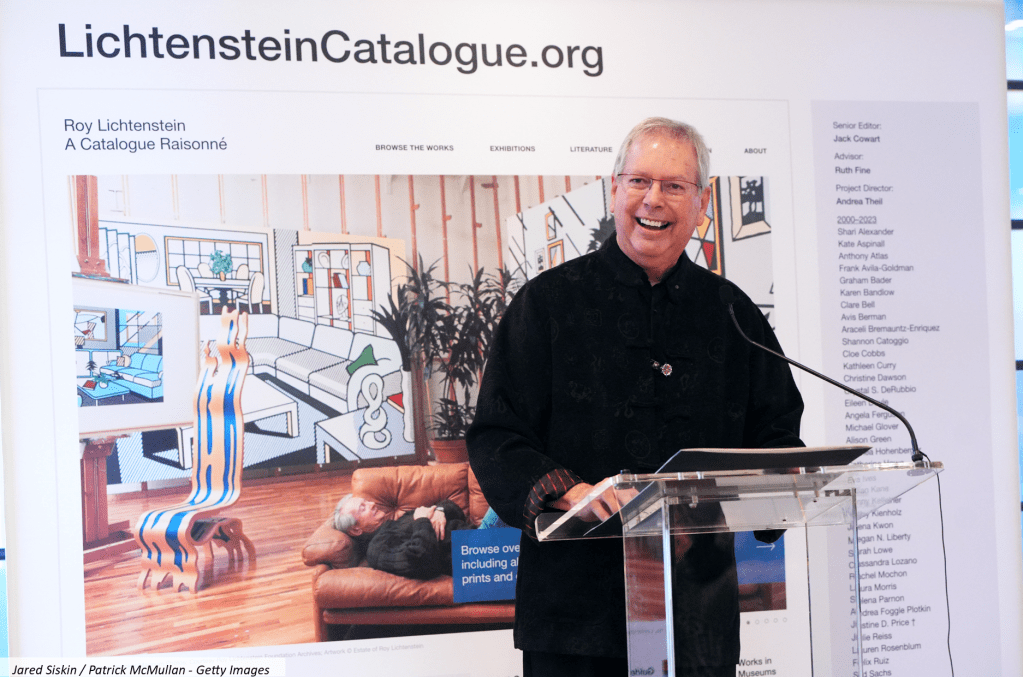

The Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, opened June 1999, preserves the legacy of the American artist. It supports exhibitions, research, and publications related to Lichtenstein’s work, ensuring its continued influence in contemporary art. Through grants and educational programs, the foundation fosters a deeper understanding of Lichtenstein’s innovative techniques and cultural impact. It maintains an extensive archive of his artworks, documents, and personal effects, facilitating scholarly inquiry and public access. On October 27th 2023, the foundation published the initial version of Lichtenstein’s catalogue raisonné online, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth. As added Centennial gifts, it took this opportunity to gift another 180 works to the already 186-artwork donation to several major institutions including the Whitney Museum, the Albertina in Vienna and the Nasher Sculpture Center/Dallas Museum of Art.

Jack Cowart is an esteemed figure in American art institutions, having held key positions at the St. Louis Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art before joining the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation as Executive Director. Cowart’s career spans curatorial work and scholarly pursuits, including celebrated exhibitions on Henri Matisse and Roy Lichtenstein, among various other European and American artists. Recognized for his contributions, he was made Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture in 2001.

- It seems that your passion for Matisse came early on. Do you remember when you discovered his work for the first time ?

{J.C.}: It all started during my Ph.D. studies in the History of Art at The Johns Hopkins University. I was in a seminar at the Baltimore Museum of Art, which was alongside the Hopkins campus given by Victor Carlson, Head of the Prints and Drawings department. He was beginning to organize his exhibition of Matisse’s drawings: “Matisse as a Draughtsman“.

The Baltimore Museum of Art holds the Cone collection—a group of Matisse paintings, drawings, works on paper and books—which is quite extraordinary. I thought some of the early Matisse drawings were misdated and this seemed like a good dissertation topic. I decided to research drawings by various early Fauve artists: Matisse, Marquet, Manguin, Camoin and Puy, to see how they were trained and when they “broke-out.” My wife got a transfer to the IBM lab in the South of France so I could use that as a base, spending time in various school archives and libraries in Paris, Geneva, Nice, and visiting the artists’ families and collectors in Europe.

- Regarding Matisse works, you seem particularly interested in the cut-outs…

{J.C.}: I did not go into that until later when I was in St. Louis and the Museum was closed for renovations. I wanted to do an exhibition and I knew I had a team of French and American friends whom I met in Paris and who had also been working on Matisse. I told them I thought we could do a small, discrete exhibition on something that had not been done in America, a limited group of Matisse gouaches découpées. By the end we realized, on the contrary, that there were over two hundred! Regardless, we did this early comprehensive catalog and a large but select exhibition with Dominique Fourcade, Jack Flam, John Neff and others. It ended up premiering at the National Gallery of Art, then traveling to Detroit and St. Louis.

Having previously lived in Nice I knew about Vence and the Musée Matisse and I loved that time in the South. However, it was certainly not a grand strategy to work on early Matisse, then work on late Matisse. It just ended up being that way, given special circumstances and a lot of good luck and contacts.

- In 1983 you curated an acclaimed exhibition on New Expressionism at the Saint Louis Art Museum. At a time when all eyes were on the American art scene, how did you understand the importance of that German movement ?

{J.C.}: As the curator of the St. Louis Museum, I generally wanted to create a context for the museum’s collection, just like I did with the Matisse exhibition. Once again, I tried to take advantage of a situation or a circumstance. It started when I organized the 1970’s/1980’s Roy Lichtenstein exhibition. We decided to travel this exhibition in the U.S., Japan, and Europe. It was held in Köln in 1982. Through all the planning, I had the opportunity to talk with the Director of the Kunsthalle about the art I was seeing in German galleries, especially Koln and Berlin. Spending a lot of time in Germany, I realized that various new painting movements were cropping up. It happens that at St. Louis we had an enormous and important group of works by Max Beckmann in our Morton D. May Collection which also included an amazing collection of other pre-World War II German artists’ paintings and sculptures. I wanted to show Mr. May and others that German art was still alive and well and that a lot of contemporary activity was happening. I saw it not only as an opportunity to work with younger artists but also to invite the Director of the Kunsthalle Siegfried Gohr to be my co-curator on the exhibition. I would not have the ability to put together that exhibition if I had not known Gohr and my knowing we could make the connections to the artists, collectors and galleries. Unfortunately, Morton May died before this German show opened but he was aware of its happening. So, I’m content I did what I could do, when I could do it.

- During your time at the National Gallery of Art, you secured the gift and promised gift of the Herbert and Dorothy Vogel collection to the museum. How did you manage to do so?

{J.C.}: It started long, long, long before. I was fascinated by Herb and Dorothy because of their involvement with conceptual and minimal artists. I don’t remember where I first met them, but they were always everywhere, all the time, and I was in New York frequently. I asked them if I could see their collection. They said: “you can come to our apartment but you can’t really see anything because it is all in boxes, it’s under the bed, it’s all over the floor…” In fact, it was even under the aquarium that could leak at any moment… So I curatorially panicked because I saw in this modest one-bedroom apartment, on the Upper-East Side but not the elegant Upper-East Side, much of the History of Art of this core period. It was stashed in that one very exposed apartment and I really wanted to rescue the art. We started having dinner at their local Chinese restaurant on a regular basis, which meant 5-hour discussions with Herb and Dorothy, time after time. This went on for some years. I was always in conversation, in New York or on the phone, with Herb and Dorothy to a point where my children began to imagine that Herb and Dorothy were grandparents that they had never known about before. They were wondering: “who are those people who are interfering with our own kid life?” It was a riot!

Being at the National Gallery, I already worked on the donation of “blue-chip” artists in the Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection. That mean we had those classical American Abstract Expressionist, Pop and Post-Pop works. Going forward I was hoping to get more artists in our collection that were of different stylistic interests and offered broader historical consequences. I did not know the exact contents of the Vogel collection, but I had heard rumors that other museums wanted to get their collection. There were challenges, Herb and Dorothy were quite specific: they did not like museums, having had some difficulties with others, and they wanted the entire collection to remain intact. I finally said to them: “Maybe we can make this go away: we are the National Gallery after all, we may have some options and this would be wonderful”. Herb and I always seemed to be arm-wrestling intellectually, arguing about the public sector of museums and the role of artists and his private feelings against the exclusionary establishment. With Herby it was obsessive, impulsive, but I can be that way too, plus so were many of my colleagues at the National Gallery.

The National Gallery had an advantage because Herb respected the fact that the museum had free entrance and he had visited it early in his marriage with Dorothy. I could not take the decision all by myself but our director at that time, J Carter Brown, was entranced by Herb and Dorothy as a kind of alternative to the Mellons and the grand patriarchies of the National Gallery. He indulged that little fantasy that I was having. Everybody was extremely friendly and it worked out very well but the arrangement of how it finally came to the National Gallery was very long, very complicated, and it was not a forgone conclusion in any way.

Nine moving vans later it somehow ended up unofficially in an unused, slightly off the radar storeroom at the National Gallery. We started to put all the various and sundry works in it to do its first-ever inventory. We had no idea what the full content was. Even Herb and Dorothy were not sure about it. They kept records but when we started getting works out of the apartment, Herb pulled out something out of a portfolio that was under the bed and Dorothy was like: “Herbie, I did not know we had that!” and Herb would answer: “Well I did! I stashed it down there” She would go “well I am supposed to keep the records!”.

At some point we found out that there were at least two stylistic parts in the Vogel collection: there was the conceptual, minimal, very cerebral and austere part and there are many painterly things with a heavy palette, plus graffiti and street art and even the surrealist things. Suddenly the Vogel Collection that I thought was very clear in my mind was actually a cross-section of scores of artists from the 60’s to the 90’s which they had bought very early and cheaply, as well as works that have been given to them by the artists in appreciation of their early commitment. They supported those artists with a small purchase at a time they needed it and they also benefited from the Vogel’s validation.

Happily, we found ways to arrange for an initial purchase in the form of an annuity and a remaining massive gift that would eventually come to the National Gallery. The preliminary front-end purchase featured a group of about a dozen works which were representative of the whole. And as we knew that Herb wanted the collection to stay together, if we had these top works, we and they knew we would get the rest as installment gifts, all for the Nation. And, remarkably, Herb and Dorothy took most of that annuity and continued to buy even more work for their collection and the Nation, so it was the gift that actually kept on giving. Again, another unintended and lucky consequence.

- You are now the executive director of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation. What was your relationship with him ?

{J.C.}: I have to go back to the exhibition I organized in St Louis in 1977. I had just finished Matisse’s cut-outs exhibition and I thought: “O.K. that’s fine, I have now worked with the estate of Henri Matisse, a dead French artist. That was nice and challenging but now I would like to work with a living artist”. I began searching around for an interesting living artist, probably American because it facilitated the situation… and one who might be nice to work with. We were involved with the Castelli Gallery and I realized that Roy Lichtenstein had a retrospective in 1969 at the Guggenheim but I began to wonder what Roy had been up to in the last ten years.

I pitched the idea to Leo Castelli and he said: “Well, why don’t you ask him?” But I did not know him personally. Apparently Roy was, in fact, very nice and Leo told him that the St. Louis Museum of Art wanted to do a large exhibition. Roy asked if I was a nice guy… I guess I was regarded as “nice enough” so we started out on a kind of blind date. I called Roy and he asked: “why don’t you just come out to Southampton?“. I agreed and we would work together on this exhibition for the next 3 years. Thus, I got to know Roy pretty well. I would spend a week in Southampton every couple of months, at his and his wife Dorothy’s house with his studio manager and his assistants. After that, for the next 20 years or so, if Roy needed something, like an essay or something to review, he might ask me. In return, Roy helped me on several museum and collection occasions. This meant I knew Roy on and off from 1977 until he died 1997. Still, I never had the ambition to be a public Lichtenstein scholar, nor to be a representative of the artist in a substantial fashion. But Dorothy Lichtenstein asked me to do a memorial speech at the MoMA.

A year and half later, with the exhibition “Roy Lichtenstein: Imágenes reconocibles: Escultura, pintura y gráfica” at the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City and eventually at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, where I was the chief operating director of the museum, I started to be more and more in contact with the estate, saying: “if there is any way I can help, let me know.” And Dorothy answered: “By the way, there is a Lichtenstein Foundation but it is only on paper. Would you consider becoming its director? You and I could start it up together”. I thought it would be a fascinating opportunity, and I must say, I did not want anybody else to get the job! So that’s the way it happened, not by design. It was the circumstance of Roy having died unexpectedly at 73 years old.

All of a sudden there was this Lichtenstein Foundation. Of course, I knew the family, I had known Roy, I knew Dorothy and I knew his two sons David and Mitchell. I felt it was a stable situation, unlike some other artists’ estates and foundations that I have worked with at the National Gallery or elsewhere where they were discords, problems and all the other things we heard about, for example Rothko or O’Keeffe. Finally, it was great that Dorothy and the Foundation Board were flexible in the fact that I did not have to move up to New York: my wife still had her career, my children were still here at the time, etc., and I could go back and forth as needed.

Knowing Roy from the late 70’s, it was fundamental to all of us that we would take our Hippocratic Oath to “cause no harm” and to make sure we kept the Foundation at a higher standard. It was surely what Dorothy and the Lichtensteins told me they wanted to do from the beginning. Since we can do this to the absolute best of our abilities, why not? Of course, at the beginning we did not know exactly what we were doing because we had no Master Plan but we did know we could build one in the coming years.

- By the way, what is the purpose and the plan of the foundation in the next few years ?

{J.C.}: We are still following our Charter Purpose which is to facilitate public access to the work of Roy Lichtenstein and the art and artists of his time. I’m very proud of the team for working tirelessly over the course of the past decades to produce the first ever catalogue raisonné devoted to Roy’s work in all media and which launched online—freely available to all—last fall. Of course, we have developed other passions along the way, including being able to have digital access to art history information because I am a geeky art historian as is everyone else at the Foundation. We like things that allow for research development and access to information. We also rescued and then donated internationally the Shunk-Kender Photography Archives, and the archivist we hired for that subsequently became our own for the Lichtenstein Archive.

At the beginning it was all our employees, who loved and respected Roy, wanting to facilitate getting as much information as possible about him into the Foundation. At some point we considered starting our own study center and little museum. Ultimately, we realized it would be better to affiliate with other institutions more broadly—nationally and internationally. So that’s when we decided to sunset the Foundation and widely distribute our holdings and our own archives and papers, this latter part being now donated to affiliate with the Archives of American Art. This will be their largest single artist archive to date, and we are now in the process of digitizing the archives before it moves physically to DC.

My job since 1999 has been to brainstorm with my board, with Dorothy, with art enthusiasts, with my staff to become, in effect, the director of a kind of “best practices” institutional policy. We have funds that we have accumulated over the years, and we want to figure out where we can help in the art world generally, as our final but ongoing legacy, and even today it is still very much a work in progress.

For example, we might like to leave an endowment to facilitate museum free entry days. We also want to facilitate conservation of outdoor sculptures. Museums have frequently come to us to ask for financial conservation support for their Lichtenstein sculptures. We have assisted them, of course, but we’d like to formalize that process. It would seem a great lasting public benefit if we could support institutions in the preservation of the sculptures not only by Roy Lichtenstein but also those by other modern and contemporary sculptors, at least in the U.S. (it is a little bit more complicated in Europe, given differences in charitable status).

I am clearly assuming that we will have other ideas that we don’t know about yet. The Roy Lichtenstein Foundation intends “to die broke”. We want to spend all the money that we have and to give away all the works that we still have, and that even includes still another group of Shunk-Kender photographs. We want to do all those things now, when we still have the funds and the energy and staff with registrars, researchers and archivists. Why wait for that last minute? As we saw during our major Centennial art gifts campaign, it can take a long time to get the communications linked, discussions and understandings made with each institution and paperwork done.

We want to have the time to enjoy this patronage, fine-tune it if necessary, and offer operational support as needed. That’s a fun way to “go out” as we hope for a long reflected sunset light of our dear Foundation, all in honor and memory of Roy Lichtenstein.